homelessness, race, and the systems that shape opportunity

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are far more likely to experience homelessness—and this reality is not accidental.

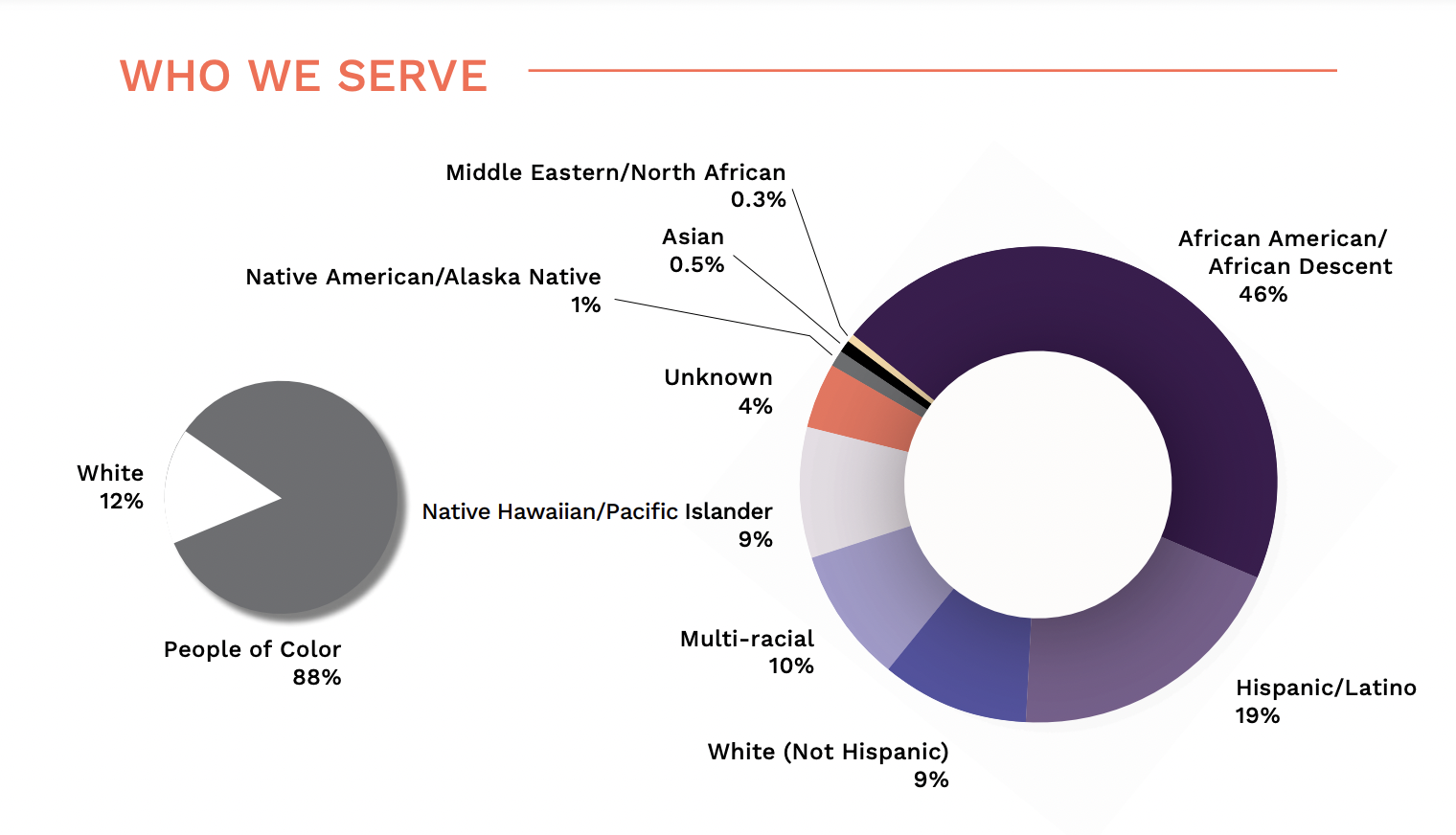

In King County, approximately 7.4% of residents identify as Black and just over 1% identify as Native American. Yet at Mary’s Place, 88% of the families we serve identify as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color. This disproportionality makes one thing clear: homelessness cannot be addressed without confronting the structural and historical racism embedded in our systems.

Housing, healthcare, education, the legal system, and child welfare have all contributed to inequities that place families of color at greater risk.

As a report from the Center for Social Innovation states:

“People of color are dramatically more likely than white people to experience homelessness in the United States. This is no accident. It is the result of centuries of structural racism that have excluded historically oppressed people—particularly Black and Native Americans—from equal access to housing, community supports, and opportunities for economic mobility.”

These realities directly affect the families Mary’s Place serves every day.

To better understand these inequities, Mary’s Place convened staff whose work spans history, data, and lived experience for a Lunch & Learn webinar to explore how racism shapes homelessness and how the organization is responding.

Understanding Historical Roots of Housing Inequity

To lay the groundwork for this discussion, Ryan Disch-Guzman, former Outreach Director at Mary’s Place, traced nearly a century of housing policy in Seattle that continues to shape today’s crisis.

In 1923, 50,000 people attended a Ku Klux Klan rally in Seattle. While Jim Crow is often associated with the South, segregationist policies were actively enforced in the North as well. These rallies trained white residents to create racially restrictive covenants, which barred people of color from owning or even living in homes across most of Seattle and King County. For Black families, the Central District became one of the few places they were allowed to live and attempt to build wealth.

A mural of Dr. King in Seattle’s Central District.

Although these covenants were outlawed in 1964 by the Civil Rights Act, the harm did not end. As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. emphasized, housing justice remained unfinished business of the civil rights movement.

Covenants were replaced by redlining, a discriminatory practice that denied loans and mortgages to residents of predominantly Black neighborhoods labeled “hazardous” on government maps. In 1966, King moved his family into Chicago’s Lawndale neighborhood to fight these practices as part of the Chicago Freedom Movement, which laid the groundwork for the Fair Housing Act of 1968, passed one week after his assassination.

King understood that unsafe, overcrowded housing was deeply tied to unequal education, limited job access, and financial instability. Housing justice, he argued, was foundational to opportunity.

Generational Wealth and Gentrification

Homeownership is the primary pathway to generational wealth in the United States. When Black and Brown families were excluded from owning homes through racist policies, they were cut off from the main mechanism for financial stability.

This wealth gap compounded over generations—and gentrification intensified the harm. During the 2008 housing recession, Black families were disproportionately forced into foreclosure. Predatory loans in communities of color were partly responsible for the housing boom and subsequent housing crisis in 2008. These loans, defined by unnecessarily high fees or risky features, such as complicated, changing interest rates, were far more prevalent in communities of color.

In Seattle’s increasingly luxury-driven housing market, many of the foreclosed homes that once belonged to Black families were purchased by outside investors—extracting wealth from Black communities and pushing families out of the city, sometimes into homelessness.

Ryan emphasized that there is a direct line from past policies to today’s housing instability, and that this history has never been fully repaired.

In fact, the nationwide homeownership rate among Black Americans today is about 45 percent, about 30 percent below their White counterparts, the same as it was when Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law in 1968.

Using Data to Advance Equity

At Mary’s Place, our mission is to ensure no child sleeps outside by centering equity and opportunity for women and families. Alyson Moon, Director of Community Impact, shared how we’re working to ensure our programs don’t perpetuate the inequities Ryan described.

“As an organization serving families experiencing homelessness, we have a responsibility to examine whether our services create equitable outcomes across race and ethnicity,” Alyson shared. “The first step is data.”

By disaggregating data by race, Mary’s Place is working to identify and correct inequities in our work. While overall outcomes may look positive, disaggregated data can uncover disparities that would otherwise remain hidden.

One example came from the outreach team’s analysis of our housing outcomes. While most outcomes were equitable, one disparity stood out: Black families were being displaced from their original communities when they found new housing at higher rates than white families.

The cause was subtle but impactful. Staff were asking white families where they wanted to live, while Black families were often asked where they could afford to live.

By shifting to a single, equity-centered question—“Where is your community of support?”—staff now support all families in staying connected to their communities. The team continues to review this data monthly—by race and geography—to remain accountable to equitable outcomes.

The Barriers Families Face Every Day

Former Senior Site Director Arlene Hampton grounded the conversation in lived experience.

“We cannot talk about homelessness—or even racism within housing systems—without also naming the core, intersecting barriers that bring families into shelter and make it harder for them to leave,” shared Arlene. “Lack of stable employment, discriminatory hiring and housing practices, limited access to healthcare, language barriers, these challenges are deeply interconnected, and they compound one another. Families arrive at our shelters already having tried to solve their housing crisis—only to encounter barrier after barrier. And while these challenges affect many families, they disproportionately impact families of color.”

Mary’s Place serves many immigrant families, including large East African, Indigenous, and Native populations, among others. While experiences vary, a common thread remains: systems that weren’t designed to support them.

Sometimes the barrier is simple—a denial letter, a missed call, or a resource unavailable in a family’s language. But repeated over time, these moments are exhausting and drain families of hope.

To help families navigate these challenges, Mary’s Place staff work closely across teams, including housing specialists, economic advancement staff, health services, and youth services.

But Arlene emphasized, Mary’s Place does not do this work alone. We intentionally partner with community-based organizations that understand the specific needs and barriers faced by different communities of color. These include partnerships with groups such as El Centro de la Raza, Mother Nation, Muslim Housing Services, and many others who bring cultural knowledge, language access, and trust within their communities.

Through these partnerships, we help families access not only housing support but also culturally responsive services that recognize family dynamics, lived experiences, and systemic barriers in ways that traditional systems often do not. These partnerships allow Mary’s Place to meet families where they are, rather than forcing families to navigate systems that were not designed for them.

This approach matters. 88% of the families served by Mary’s Place are families of color, and every week, staff see families make meaningful progress when systems respond to their realities.

Moving Forward With Intention

When asked what more could be done to reduce racial disparities in homelessness, Alyson returned to one core principle: centering the voices of those most impacted.

“When programs and policies are shaped by the people they are meant to serve, they are far more likely to meet real needs and eliminate inequities,” she shared.

By naming historical harms, using data intentionally, learning from families, and centering community voice, Mary’s Place continues working toward a future where every family—regardless of race or background—has access to safe, stable housing and the opportunity to thrive.

Check out this recorded panel discussion, and more, in our webinar library!